In 2019, the Historic Fredericksburg Foundation Inc. hosted a three-part lecture series on the city's historic Renwick Courthouse to bring renewed attention to this beautiful and unique gem and its uncertain future.

Though the 1852 courthouse is locally understood to be an important building, HFFI's series sought to fill some of the gaps left by the historic structures report completed in 2016 by examining its historical significance within appropriate contexts.

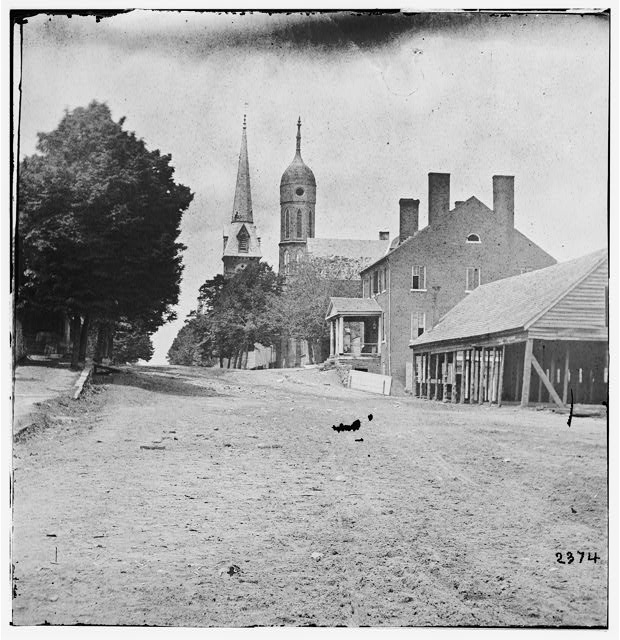

Locally and within the region, the building is the embodiment of the American judicial system, bearing witness to the work of countless civil servants, legal rituals, law enforcement, and citizens' ideas of justice for more than 150 years. Local leaders' determination to build the latest and greatest architecture with the country's leading designer to serve as the heart of this city reflects the community's civic pride and character.

At the regional and state level, the courthouse served as a stronghold during a period of national crisis. It was the place where the town's voters approved Virginia's secession from the Union and later was one of the most important points from which communications were exchanged during one of the most important battles of the Civil War.

The courthouse was used to temporarily house people who escaped slavery, to detain military prisoners, and as a hospital to shelter and care for the wounded and dying during the conflict. Years later, it was also where the local Freedman's Bureau Court met in an effort to administer equal justice for African Americans in the war's aftermath. Later still, in the mid-1880s, it was where congregants of Shiloh Baptist Church held religious services prior to their division into "Old" and "New" sites.

James Renwick, Jr.'s design of the building constructed between 1851 and 1852 by local contractor William Bagget is a truly unique piece of American art and architecture.

One of the nation's most important and influential architects during the mid-19th century, Renwick's design for our courthouse was itself revolutionary. Its deliberate use of Gothic Revival styling for a civic building illustrates a controversial debate held in fashionable circles here and in Europe as to what style and type of architecture our country should embrace.

A generation earlier, Thomas Jefferson sought to convey America's democratic ideals through the architecture of ancient Rome. But Renwick and other leading designers of the day looked to medieval cathedrals as reflections of our cultural heritage, arguing that the Gothic style was more appropriate, as seen in monumental buildings like England's Houses of Parliament at the Palace of Westminster (built 1837–1860).

Renwick's first building, Grace Church (1846) in New York, and later works such as the Smithsonian Castle (1855) and St. Patrick's Cathedral (built 1858–78) embraced the Gothic Revival style. In fact, his designs were so influential that many architectural historians credit him with making the Gothic Revival style popular in a wide array of church denominations across the country for more than 100 years!

The Renwick Courthouse is truly the most architecturally significant building in town. What we do with it, and how we support its second lease on life, is one of the most important preservation decisions our community and city will make. It is critical that this decision be made with great transparency and significant input from concerned citizens.

The only courthouse attributable to James Renwick, Jr., this building reflects an artistic revolution that yields national historic significance. It would be a terrible mistake to give this treasure away lightly. It is not merely square footage to be leased for a profit and a list of repairs to be offloaded; it is a formidable pillar of our community-past, present, and future.

HFFI believes that an open and honest dialogue about this unmatched historic asset is critical in any decision-making process.

The most common questions from attendees during our lectures revolved around what the 2016 Historic Structures Report omitted: a thorough analysis of historic significance and original materials, and what future uses are best suited for it based on its architectural significance and condition.

From a preservation perspective, less intensive uses are preferred for heirlooms of this order. And many would say that we could not find a better place to serve as our Visitor Center to showcase the history of our community and the historic architecture that shapes it.

In the 1990s, the city levied a two percent tax on gasoline sold in town to support the rehabilitation of the train station, raising $800,000 in a single year. What prevents us from taking similar proactive and progressive steps to ensure a historically sensitive rehabilitation (if not restoration!) of our Renwick Courthouse?

We hope that the concerned citizens of Fredericksburg will continue to participate with us in that discussion with city staff moving forward.

Danae Peckler is an architectural historian and HFFI board member.

A version of this article was originally published in The Free Lance-Star